Quicksilver Messenger Service and Nicky

Hopkins

Albums reviewed on this page: Quicksilver

Messenger Service, Happy Trails, Shady

Grove, Just for Love, What

About Me,

Tin Man Was a Dreamer, No

More Changes.

More consistent than the Airplane

and more varying than the Dead, but with the same instrumental

prowess, Quicksilver Messenger Service were a first tier Frisco band

that has been lost in the shuffle. In America the blame is easy

to fix - the group had only one single that approached being a hit,

"Fresh Air", and it only cracked the Top 50. Classic

rock programmers tend to ignore the group's string of four albums in

the Top 30, from Happy Trails to What About Me.

As for the band itself, they say you can never go back, but that is

exactly what Dino Valenti did. During the group's really early

days he got busted for drugs and wound up in prison. Music and

drugs seem to be the common things in his life, as he previously had

sold song rights to pay for legal defense. With Valenti out of

the way, Quicksilver focused on the intertwined guitars of Gary

Duncan and John Cippolina, with David Freiberg on bass and Greg

Elmore on drums. The band focused on acid-rock and folk, with

an interesting taste in instrumental passages. Cippolina's

guitar has a distinct ringing tone which gives it a unique sound.

Of course, it couldn't last, as Duncan soon left to join a freed

Valenti in some project that proved to be a non-starter. In

what has to be the most inspired move around, the band coaxed British

session pianist vet Nicky Hopkins into the fold, and the move paid

dividends immediately on Shady Grove. But then Valenti

and Duncan both returned and everyone played together for a

while, with Valenti taking charge and scoring the aforementioned

almost hit "Fresh Air". But listening to Just for

Love and What About Me it is pretty obvious that Valenti

really crowded the group, and it is no surprise that Cippolina,

Freiberg and Hopkins all left after one more album. After one

album with scrubs the band called it quits. Cippolina formed a

group named Copperhead, which released one album, while Freiberg went

over to Jefferson Airplane. Hopkins went

back into session work, and had an unsuccessful solo career.

God knows what Dino Valenti did. Probably more drugs.

In

the American game of baseball there is currently the notion

circulating of a level of playing referred to as "replacement

level." The idea is that those people who perform at or

under this level can easily be replaced by someone who is at

"replacement level" who probably costs a lot less.

This is somewhat analogous to the position of sessionmen in rock

music. If a member of your band is not playing up to

"replacement level" (or in the case of John's Children, the

entire band) simply have session people take their place on the

recording. This oversimplifies things, but there were a good

number of people who were good enough (i.e., "replacement

level") to make their living by filling an often anonymous

role. The best of them, people like the Keys-Horn-Price horn

section, Jimmy Page and Nicky Hopkins, were often far above

"replacement level" and instead of simply filling a role

they augmented recordings musically (as opposed to simply

sonically). Essentially, the best session guys were more than

just spare parts, and Nicky Hopkins was the premiere session

keyboardist in the late 60s and 70s. His style is mainly

R&B/rock, but he could handle all sorts of roles - from a Kinks'

harpsichord session to a loopy Giles,

Giles and Fripp session to a pounding Stones one. He was in

the Jeff Beck Group, he was in

Quicksilver Messenger Service, and he turned down a chance to join

the Rolling Stones. His own small output is terribly uneven,

but Tin Man Was a Dreamer is worth checking out - along the

lines of the whole post-Delaney & Bonnie countrified rock sound.

Personnel: John Cipollina (guitar), Gary Duncan (guitar), David Freiberg (bass, vocals), Greg Elmore

(drums), Dino Valenti (guitar, vocals). Valenti imprisoned before the band recorded.. Duncan

left after Happy Trails, replaced by Nicky Hopkins (piano).

Duncan then returned with Valenti in 1970.

Cipollina, Freiberg and Hopkins quit mid-1971.

Band ended 1973.

Nicky Hopkins: Revolutionary

Piano (1966)

I

don't think I'll be seeing this. Ever. EZ listening material,

not revolutionary.

Quicksilver

Messenger Service (1968), ****

Quicksilver

Messenger Service (1968), ****

Quicksilver

had been around the San Francisco scene for a few years before

recording their eponymous debut. The

straightforward production is rather surprising given

when it was recorded, the band perhaps having learned a lesson from

some other

local groups. Instead of

hazardous psychedelia, QMS is a guitar-led acid-folk album

that stays focused while it chugs along (the imprisoned Valenti's

sole contribution "Dino's Song" is a good example).

As for musical influences, QMS includes everything up to the

kitchen sink - folk, jazz, Spanish classical, country, blues all

thrown together, giving the band a diverse sound not unlike Love's

Forever Changes, but much more electric guitar based.

Lead guitarist John Cipollina coaxed a unique ringing twang out his

instrument ("Pride of Man"), giving Quicksilver an

identifiable sound, but the entire is tightly knit (the early

country-rock "Too Long"). The longer tracks are of a

lesser quality, but barely. Cipollina and Duncan trade off

frequently, which creates some good moments, such as the instrumental

"Gold and Silver": the inevitable "Take Five"

based song transferred into 6/8, which could have appeared on This

Was.

The other example is the

slightly sprawling "The Fool", which sounds like the

soundtrack to a Western (at one point a guitar is wah-wahed into

sounding like a rattlesnake, while occasionally a whip is heard),

before panning out with some fairly lame 60s lyrics. Otherwise,

everything on QMS is extremely well done. Energetic,

entertaining and featuring some strong guitar work. In good

Frisco style, who did what is not shown. Produced by Nick

Gravenites, Harvey Brooks, and Pete Welding.

Quicksilver

Messenger Service: Happy Trails (1969), ***

Quicksilver

Messenger Service: Happy Trails (1969), ***

The title does

not reveal this, but Happy Trails was mostly recorded live.

It is a wrongful game of catch-up: the dated experimentalism

Quicksilver successfully avoided on their debut is present. The

first side is the "Who Do You Love Suite", a

rendition of the Bo Diddly tune divided into instrumental solo

sections. Thankfully, the

band dropped Diddly's infamous rhythm fairly early on, and stretch

out into some bluesy/jazzy soloing. At its core, however, the

suite collapses first into harmonics (which is, well, unusual)

and then into Freiberg's violin scrapings while the crowd noise is

viciously panned ("Where Do You Love"). Back in the

studio, Duncan wrote another track that sounded like a Western

soundtrack (the instrumental "Calvary"),

which is structured as the suite's inverse; that is, it has a

worthwhile song portion in the middle, but is bookended by abstract

noises and instrumental diddling. The other live tracks show

them to be an excellent hard rocking San Francisco group ("Maiden

of the Cancer Moon" and Diddly's "Mona"). Only

their instrumental craftsmanship saves this album.

Quicksilver

Messenger Service: Shady Grove (1970), ***1/2

Quicksilver

Messenger Service: Shady Grove (1970), ***1/2

Their first

album with Nicky Hopkins, and his impact is enormous. Of

course, I should hope so, as he replaced Duncan,

who was Quicksilver's main songwriter. But a change of musical

scenery (diffusing the musical focal point away from the guitar) did

everyone good, and producer Nick Gravenites stepped in to co-write

with group members. Do not be deterred by the first two songs

on this album, which feature iffy vocals and are not astounding.

The third, "3 or 4 Feet From Home", is a blues stomper with

guitar and piano both wailing away. Hopkins

is the center of the next two tracks, "Too Far"

and "Holy Moly", and they are even better. The former

is a real classic, and the latter is also a good time, despite

similarites with Donovan's "Atlantis". Shady

Grove's back

side is more experimental, with Cipollina more content to play around

with weird effects than actually soloing (the coda to "Joseph's

Coda"), and some traditional (the nice "Words Can't Say").

But the real stuff is the sad "Flashing Lonesome", with

interesting interplay between Hopkins and Cipollina. Finally,

Hopkins' contributed the uncharacteristic (for a West Coast band)

"Edward (The Mad Shirt Grinder)", a faintly jazzy keyboard

masterpiece. Just listen to the rest of the band try to keep up

with him! If you like piano-based rock songs (and I don't mean

bastards like Billy Joel) Shady Grove delivers, just don't

expect Dead or Airplane-like

material. (Capitol SM-391 LP)

Quicksilver

Messenger Service: Just for Love (1970), **

Quicksilver

Messenger Service: Just for Love (1970), **

Like a good

Mafia family, Quicksilver welcomed back Dino Valenti after he paid

his debt to society. He immediately became the group's central

figure, which was unfortunate. It was not an ideal match; Valenti had

been a folk singer/songwriter in the pre-Byrds era, while

Quicksilver's talents were more instrumental and loose. Thus,

Quicksilver became a vehicle for Valenti's physical and musical

voices. His physical voice is a few shades of annoying-- an

offputting nasal twang that cuts through the air. Just for Love's

production only exacerbates this; the band moved to a remote Hawaiian

location to record the album, and it sounds like it was recorded in

the Hollywood Bowl without microphones. This results in obvious

mixing problems, and the band sounds dispersed and distant. This in

turn makes Valenti's vocal dominance all the more scary--he must have

had quite the pair of lungs. His musical voice dominates the album,

leading Quicksilver into latin-jazz ("Fresh Air" or the

languid "Gone Again"), New Age instrumentals ("Wolf

Run") or needlessly

long bluesy compositions ("The Hat" with some

over-the-top vocals or "Gone Again"). Sure, the rest of the

band might have offset this with their usual wizardry, and they may

have done so, except they are not really audible. Cippolina gets one

nice instrumental track ("Cobra"), but that is about it.

Two of the shorter tracks are more tolerable - the blues-rock of

"Freeway Flyer" and the Santana-like "Fresh Air"

which became a semi-hit. The song's succees seems more the product of

dumb luck than any particular talent, although it is the one track

where the guitars are the clearest. Somehow the band managed to

squander the talents of Duncan, Cippolina and Hopkins on this folly.

Under-rehearsed, under-recorded, and underwhelming.

Quicksilver

Messenger Service: What About Me? (1971), **1/2

Quicksilver

Messenger Service: What About Me? (1971), **1/2

Only partially

composed of Hawaiian wilderness tracks, and Quicksilver benefitted

from the return to a real studio. Valenti's dominance over

Quicksilver' direction continued (the Santana-like

title track or the cocktail jazz of "All In My Mind" are

the most successful examples) with only a few nods towards their

former style ("Baby Baby"), and the execution is poor on a

few fronts. Valenti really sounds like a marijuana cowboy - his

vocals are constrained, twangy and really laid back. His songs

are much more conventional in construction than on Just for Love,

but the band does not use the provided space to stretch out,

resulting in the distinct feeling that many of the tracks have been

padded out in length (the spacey folk "Long Haired Lady",

"Call On Me"). It also does not help that Cipollina,

Freiberg and Hopkins were only somewhat involved, although each

placed one song on

What About Me?, with Hopkins's "Spindrifter" being

yet another piano instrumental classic. Mark Naftalin

(ex-Butterfield Blues, Electric Flag) contributed piano on some

tracks and Duncan is credited with some bass. Percussionist

Jose Rico Reyes was also brought in and did a good job in places.

All in all, there are a few good spots, but the rest is just eh.

No credited producer.

Quicksilver Messenger Service:

Quicksilver (1971)

Cippolina,

Hopkins and Freiberg's last album.

Quicksilver Messenger

Service: Comin' Thru (1972)

Nicky

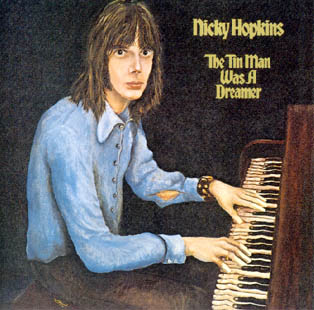

Hopkins: Tin Man Was a Dreamer (1973), ***

Nicky

Hopkins: Tin Man Was a Dreamer (1973), ***

Hopkins' first

solo album is rather peculiar. It is not really a

singer-songwriter album, although many of the tracks are apparently

reflective of his life a session pianist. In fact, Hopkins sang

on only about half the tracks, with the expressive Jerry Williams

(aka Swamp Dogg, who also helped write some of the songs) handling

the rest. This makes Hopkins sound like a guest on his own

record, but that the role in which he always seemed the most

comfortable. Tin Man is mainly piano-rock,

alternating between orchestrated romantic numbers and more driven

boogie or down-home rock numbers. As a pianist Hopkins had a

distinctive style, but his voice was breathy and his range rather

limited. It works well on the sad-sack "The Dreamer"

which sounds like it could be from Kermit the Frog on Broadway,

and on the strong "Waiting For the Band". Out of the

Williams numbers "Banana Anna" is a boogie with the

vocalist occasionally shouting his way to a good time, and "Shout

It Out" is another strong "rock" number. On the

downside Hopkins's overly earnest vocals make it hard to determine if

"Lawyer's Lament" is poking fun or not. The

instrumental tracks are all decent, and the remake of "Edward"

adds in a wonderful Bobby

Keys sax break. Of course, the majority of the

people on session men - ranging from the famous (Keys-Horn-Price horn

section and Stones guitarist Mick Taylor), the usual faceless crowd

(Klaus Voorman, Chris Spedding, Ray Cooper), the future famous (Tubes

drummer Prairie Prince), to the mysterious (George O'Hara, or should

I say George Harrison, diddling around on slide). So, this

album is generally good, but it's never really clear as to who is in

charge - with Williams singing and Hopkins's piano not really

up-front a lot. Produced by Hopkins and David Briggs.

Nicky

Hopkins: No More Changes (1975), **

Nicky

Hopkins: No More Changes (1975), **

Oh dear.

Remember how I said Hopkins limited voice only worked in certain

situations? While not an

abysmal vocalist, on

No More Changes he went all out, and at his best sounds like Ronnie

Lane's bad side

("Refugee Blues"). Combine that with a

no-name backing band and the results are something strangely akin to

a misbegotten karaoke recording ("Wild You" or the vocally

frightening opener "Sea Cruise"). Whereas Williams

could sing and wrote a bunch of lyrics on the previous album, here

Hopkins relies on a couple of covers (among them Jackie De Shannon's

"Hanna", "Lady It's Time to Go") or his wife's

rather bland lyrical skills. Only once does he attempt to

recapture the sad aura of his last album ("No Time") and it

doesn't work that well. Nor are his instrumentals very

interesting - the exception, "The Ridiculous Trip", is

simply Tin Man's "Speed On" without lyrics.

The most bizarre thing of all is "Mornin I'll Be Movin' On"

which sounds faintly like disco. Overall, the album continues

his brand of slightly countrified piano rock, but not in a fun way.

The guilty parties (certainly "replacement level") are Eric

Dillion (drums), Rick

Wills (bass), David

Tedstone (guitar), and Michael Kennedy (guitar). Produced by

Hopkins, John Edwards and Mark Smith. (Mercury LP SRM-1-1028)

In case you

were wondering, if this had been two LPs it would have gotten half a

star lower.

Quicksilver Messenger Service:

Solid Silver (1975)

A

reunion record.

Gee it's awful,

waiting around, so back to the Music Page...

Quicksilver

Messenger Service (1968), ****

Quicksilver

Messenger Service (1968), ****

Quicksilver

Messenger Service: Happy Trails (1969), ***

Quicksilver

Messenger Service: Happy Trails (1969), ***

Quicksilver

Messenger Service: Shady Grove (1970), ***1/2

Quicksilver

Messenger Service: Shady Grove (1970), ***1/2

Quicksilver

Messenger Service: Just for Love (1970), **

Quicksilver

Messenger Service: Just for Love (1970), **

Quicksilver

Messenger Service: What About Me? (1971), **1/2

Quicksilver

Messenger Service: What About Me? (1971), **1/2

Nicky

Hopkins: Tin Man Was a Dreamer (1973), ***

Nicky

Hopkins: Tin Man Was a Dreamer (1973), ***

Nicky

Hopkins: No More Changes (1975), **

Nicky

Hopkins: No More Changes (1975), **