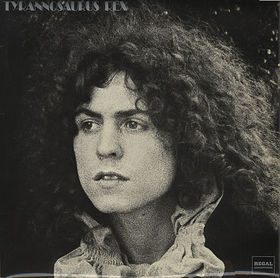

Tyrannosaurus Rex, aka T. Rex

aka

TR aka Mr. Rexasauaurs aka Tyranny of the Soral Rexus

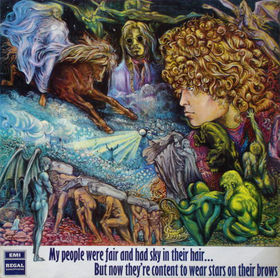

Albums reviewed on this page: My People Were Fair and Had Sky in Their Hair

. . . But Now They're Content to Wear Stars on Their Brows,

Prophets, Seers and Sages, Unicorn, A Beard of Stars.

Tyrannosaurus Rex

was a two-person 60s freak folk band that gained more complex

production, less muddy songs and eventually electric guitar(!) in their

lifetime. Upon reaching the age of maturity for bands, which

in

this case scientists have calculated to be somewhere around two years,

the band shortened its name, shed its exoskeleton and generally

improved its outlook. This was no mere Hollywood ploy of

giving

the hot girl glasses, a frumpy wardrobe and a haircut that North

Dakotas found outdated. No, evolution was right to force

changes

upon T.R.,

as its earliest

incarnation is an awful, awful mess. The plot

outline is

this: Marc Bolan on acoustic guitar and mushmouth elaborate vocals and

S.P. Took on assorted complicated percussion (not drums).

Enter

more and more studio overdubs, as Bolan focuses. Exit Took,

replace with hipster M. Finn, continue prior trends. Enter

electric guitar, more overdubs and then the sword comes down, forename

shortened, numbers doubled and the pawn is knighted. Fin.

I've listed the T. Rex

albums I have below, but I'm not going to review them immediately.

Of course, the evolution to electric music was actually a

return

for Bolan, who had been with mod-rock incompetents John's Children.

Personnel: Marc Bolan (guitars, vocals), Steve Peregrine Took

(percussion) replaced by Mickey Finn (percussion) in 1970.

Rhythm section added to form the corpus of T. Rex.

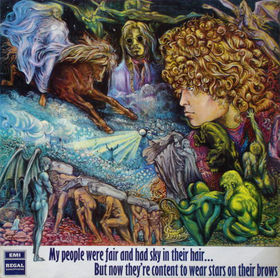

My

People Were Fair and Had Sky in Their Hair . . . But Now They're

Content to Wear Stars on Their Brows (1968), *

My

People Were Fair and Had Sky in Their Hair . . . But Now They're

Content to Wear Stars on Their Brows (1968), *

It's

my own fault. I should have realized stereotypical images of

mind-blasted hippies with bongos derived from some real person,

somewhere, and that it was only a matter of time before I encountered

it. It turns out Tyrannosaurus Rex were those guys, and damn, were they

hard to endure in their original form.

Their

musical approach is simple: Bolan on acoustic guitar and slurred,

stratosphere vocals, with Took on a variety of drum-like instruments,

with few/no overdubs. Also, a tanker full of drugs, raising

Bolan

to the stratosphere and making his vocals hard to understand.

This approach alone isn't bad; what makes it intolerable is

that

Bolan's songs have few hooks, and his playing is not enough to maintain

interest. Well, surely they were a lyrics band, you might

think.

First, admittedly I'm not English, but Bolan is so sky high I

can't tell what he's singing most of the time. Second, he

repeats

himself a lot, caught in the rhythm of his words, creating the feeling

of a jam without the actual jam. If they were a lyrics band,

perhaps I, an unbeliever, am not affected. The band did have

some

unique aspects

- Bolan's periodic ruffled falsetto, and Took's non-traditional

(non-Western) rhythms and instrumentation. The songs are mostly

indistinguishable, such that I didn't realize I was listening to the

wrong side of the album at one point. A few songs are roughly

blues ("Hot Rod Mama" and "Mustang Ford") and "Scensof" is folky, the

rest populate some magical monochrome dream world in the band's head.

The album closes with "Frowning

Atahuallpa", featuring

Bolan singing Hare Krishna, before breaking into a long children's

story excerpt. I'm sure the dozens of listeners in their

smoke-filled rooms appreciated the sudden shift into child-land from

Bolan's endless vocal grooves. It is the best part of an

album which would sound impossibly dated within a few years.

Produced by Tony Visconti, and it reached the UK top 15.

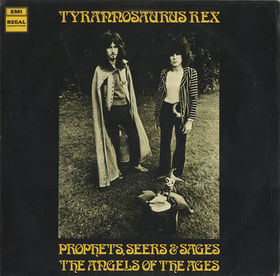

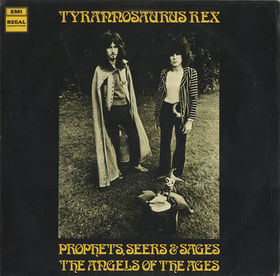

Prophets,

Seers and Sages (1968), *1/2

Prophets,

Seers and Sages (1968), *1/2

Minor

improvement, although I've left off the full (totally ridiculous) title.

You can distinguish the songs a bit easier.

The opening "Deboraarobed" is an actual song, with the tape

run

in reverse at its end so you hear the whole thing backwards.

It

isn't awful, so that's a step up, a few other tracks resemble songs

("Conesuela" and "Salamanda Palaganda" among the chosen ones).

The production is also a bit fancier; some overdubs and the

like,

but it still suffers from Bolan's ingesting so many drugs that he

communes with the spirits of Tolkien and Indian mystics and gains the

idea that two chords and some nonsense syllables construct a song.

Also, I still cannot understand most of what he says.

If

you want a man's occasional giggle laughing over an elementary mixture

of Indian and English folk music, search no more. Visconti

produced again, and it did not chart.

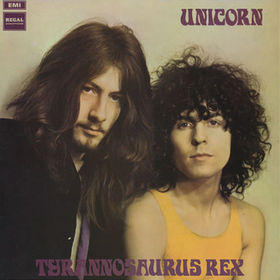

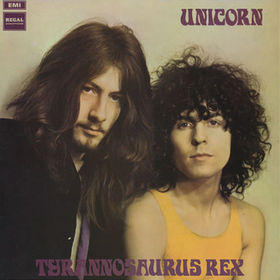

Unicorn (1969),

**

Unicorn (1969),

**

The

upward swing continues, aided mostly because Bolan fashioned his

materials more closely into songs,

and increased overdubs give the material

more depth.

Bolan still relied a bit too much

on attempted sing-along portions ("Stones for Avalon") and his

grandiose lyrics, still often sung without fully

formed consonants. But even though the approach was often

the same, Bolan is usually more intelligible and the results

are

often better. Most of Unicorn

is recognizable as acoustic folk songs, a number of which are decent

("Seal of Seasons", "She was born to be my Unicorn", "Like a White

Star, tangled and far, Tulip that's what you are", "Nijinsky Hind").

Even the acoustic break at the end of "White Star", which

devolved into another sky-high excursion, works. Part of the

(relative) success is due to Visconti's production, which is more

fleshed out (although

no drums), such that the song with the boldest sound is also clearly

the most well-thought out (and best): "Catblack" with Visconti on

clanging piano, shows Bolan using a catchy chorus in something

close to a 50s pop song, instead of repeating it in a mushmouth piece

of

claptrap. Nor did Visconti rely on many production tricks,

occasionally things like sped up vocals (the Teletubbies get high

intro to "'Pon a Hill") or running the tape backwards (the gentle "The

Throat of Winter"). Even with

few tricks, it is clear that Bolan aimed this at his era's freak folk

fans, even giving a number of minutes over to DJ John Peel reading a

children's story ("Romany Soup"). This was also Took's last

album

with the band, and he's rather good at his appointed tasks of difficult

percussive rhythms ("Eueops of Damask"), as well as providing

high-pitched backing vocals and other instruments when required.

For all Unicorn's

progress, Bolan

still could not consistently write good songs, instead relying on his

florid lyrics and hippie vibes, and much of the album is underwritten

and disposable. Yet, even if the whole thing is indistinct,

it

remains a sort of harmless comfort food for listeners. It

reached

#12 in the UK, for what that's worth.

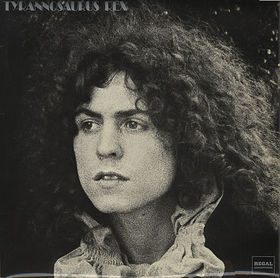

A

Beard of Stars (1970), ***1/2

A

Beard of Stars (1970), ***1/2

or

Electric Rex, as the instrumental prelude announces. But it's

no

simple

substitution; Bolan wisely augments his folk music with electric

lines from his new axe. Almost everything is still

based on acoustic guitar, and Bolan isn't using the electric in any set

fashion - playing over the rhythm, taking rock interludes ("Pavilions

of the Sun", "Lofty Skies"), but he clearly knows how to play the

instrument well. The underlying material is clearly from the

same mind

as

the earlier albums, but far more cohesive and understandable.

In

other words, Bolan stopped writing songs where the music was an

underwritten frame trying to support his elaborate lyrics.

(Certainly, a lot of folk music focuses on lyrics at the

expense

of music, but Bolan took this direction to extremes, and then sang

dada). Here, the mixture is so markedly better that it's a

bit of a

shock, and the electric additions make it better: "A Daye

Laye", "By

the

Light of the Magical Moon", "Lofty Skies" and "Woodland Bop" are all

very good songs that could have been lost in the mental tye-dye of

earlier versions of Tyr. Rex.

Forerunners of their later sound show up, such as the high

pitched backing vocals and wailing electric guitar lines on "First

Heart Mighty Dawn Dart" or the title track. Micky

Finn, the

new percussionist/sometimes bassist/backing singer/cool looking

hipster-dude, is less of the same from Took - less complicated, less

unusual sounding, but this creates a space for Bolan

to dub

electric on top of the basic duo. But it's not

just electric

guitars, as Bolan was

also using organs more, leading to oddities like the droning

organ+percussion "Organ Blues" or the ominous "Wind Cheetah".

Yet, in the end, it is

all about electric guitar: the album's

closer "Elemental Child" is that which the opening prelude foretold:

Bolan playing something like chugging electric blues-rock and then

breaking into an extended solo/rhythm for over six minutes.

If it were not for Bolan's

voice, you would be hard pressed to place "Elemental Child" on this

album, and certainly not on anything before it. It's a

suitable

ending, an impressive coda and an arrow.

T.

Rex,

or The Band Gets Rhythm

T. Rex (1970)

Electric Warrior

(1971)

The Slider (1972)

Tanx (1973)

My

People Were Fair and Had Sky in Their Hair . . . But Now They're

Content to Wear Stars on Their Brows (1968),

My

People Were Fair and Had Sky in Their Hair . . . But Now They're

Content to Wear Stars on Their Brows (1968), My

People Were Fair and Had Sky in Their Hair . . . But Now They're

Content to Wear Stars on Their Brows (1968), *

My

People Were Fair and Had Sky in Their Hair . . . But Now They're

Content to Wear Stars on Their Brows (1968), * Prophets,

Seers and Sages (1968), *1/2

Prophets,

Seers and Sages (1968), *1/2 Unicorn (1969),

**

Unicorn (1969),

** A

Beard of Stars (1970), ***1/2

A

Beard of Stars (1970), ***1/2